The Collatz Conjecture is a famous unsolved problem in Maths. It is named after the German mathematician Lothar Collatz, who proposed it in 1937. Its set up is easy to understand;

Choose a positive integer.

If even, half it

If odd, multiply by 3 and add 1

Repeat with your new integer

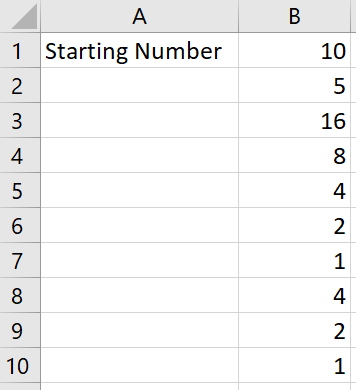

For example, starting with 10, we get 10à5à 16à8à4à2à1à4à2à1 etc

Collatz’ conjecture is that every positive integer will always reach 1. It has been shown that the conjecture holds true for every positive integer up to 2.95×1020, but no proof has been found to show that it holds for all positive integers.

The ‘low floor, high ceiling’ nature of this conjecture means that it lends itself well to an investigative project with students. It is also a good topic for students to use spreadsheets to investigate. I trialled this project with my Year 8 set 1 class. I’m planning to also trial it

with some less confident mathematicians next month. Described below is the

method I used, and some of the results and analysis. This will act as a

reminder for me for when I do it next year but also, I hope, a useful resource which

may encourage you to give this project a go with your students.

I recommend introducing the conjecture with pen and paper first so students get the hang of it. A map can be built showing the various routes numbers take to get to one.

We then moved to spreadsheets. Students worked down in a column but were calculating the operations in their heads and inputting the answer each time. Some tried an IF statement but to no avail. The IF statement that distinguishes between odds and evens is =IF(ISEVEN(B1),B1/2,B1*3+1). This ‘if statement’ dictates that if the number in the cell B1 (the cell above the selected one) is even, the number should be divided by two. However, if the number is odd, it should be multiplied by three and increased by one. This formula can then be repeated down the column.

I didn’t expect the students to find this themselves so I gave them this IF statement and they were appreciative of the power of excel after spending time having to work out the sequences by hand.

Changing the starting number will automatically generate a new sequence. Comparing different starting numbers is interesting and this can be done by copying across columns for other starting numbers.

One of the most interesting parts of this investigation is to determine how many steps different starting numbers take to get to one. Again, there is an excel formula for this which I gave to students. It uses the X Match function, and for the spreadsheet below it would be entered as =XMATCH(1,B2:B1000,0,1)

This function will find a specific value within an instructed range (in the case of this example, B2:B1000). The first ‘1’ is the value for which the programme is instructed to search. The ‘0’ instructs the programme that a specific value is needed, not just cells that contain data within a certain range. And then the final ‘1’ describes the order in which the programme should search the data (in this case, first-to-last).

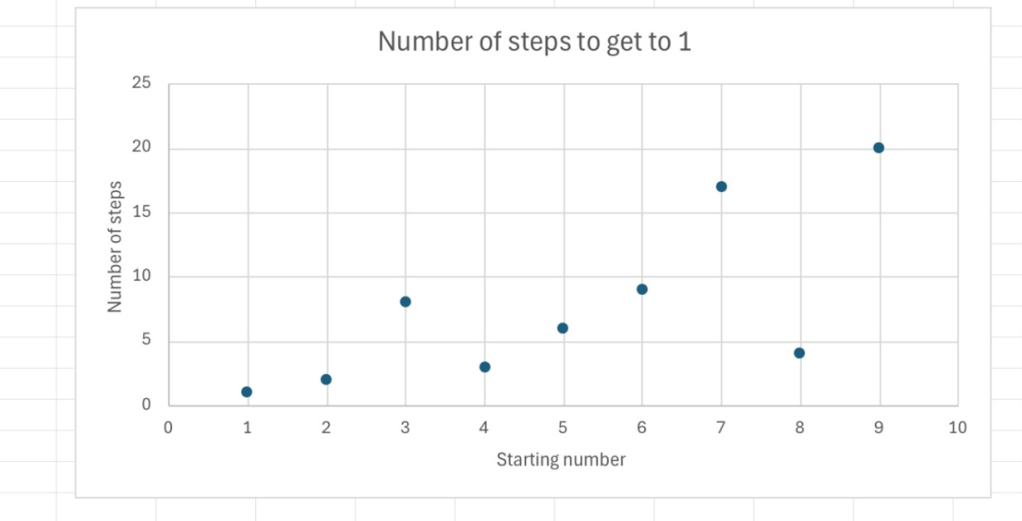

Students graphed their results showing how many steps the numbers 1-10 take to get to one.

And here for starting numbers from 1-100

The above graph provoked some questions. Some students noticed that some consecutive starting numbers took the same number of steps to reach one. For example, the numbers 36,37,38 all take 22 steps and, incredibly, the numbers 98 – 102 all take 26 steps! We couldn’t explain why this happened but we enjoyed the surprise!

Many students correctly identified that powers of two reached one very quickly. We couldn’t explain why some numbers took so many steps to reach 1. Some students analysed different types of number and the mean average number of steps it took to reach one. If we consider starting numbers from 1-100, this table summarises the results;

| Type of Number | Mean average steps to one |

| All | 32.4 |

| Odds | 41.5 |

| Evens | 23.3 |

| Squares | 15.6 |

| Primes | 44.4 |

I then encouraged students to form their own conjecture by tweaking the rules slightly. By simply changing the x3+1 to x3+2, students found that most starting numbers will never reach one (or decrease. With the exceptions of powers of two (since those can be continuously halved until 1 is reached) and 1 itself, the sequence can only keep increasing, e.g.

3 → 11 → 35 → 107 → 323 → 971 →…

Observations such as this led to good discussions about odds and evens. Students generally agreed that Collatz’s original conjecture was a good vehicle for turning odds into evens.

Most students enjoyed this investigation, and the subsequent write-up, and I look forward to doing it again soon. Any questions or comments warmly received – thanks.

On wikipedia it says of the collatz conjecture that Krasikov and Lagaria found using a computer that in a large enough interval from 1 to X there are at least X to the power of 0.84 numbers that reach 1. Your plot of 100 numbers has 84 numbers at the bottom !

LikeLike